|

History

Fleet Air Arm of the United States Navy

(Pages 7-12)

Aviation became an authorized interest of the United States Navy on December 23, 1910. There were, on that day, no pilots,

no planes, not even an articulate plan for aviation development.

Certainly no one dreamed that within a generation, 25 per cent of naval personnel would be concerned with operations neither

on sea or land but - in the air! But on that 23 December - a landmark, even the birthmark of naval aviation - the Navy Department

granted Lieutenant T. G. Ellyson permission to learn how to fly. And Lieutenant Ellyson was to receive his instruction under

the guidance, and at the expense, of the Glenn H. Curtiss Company, for the Navy had no equipment, no funds for any such activity.

Comparisons may be odious and statistics may be boring, but they can be a bit startling: in the Naval Appropriation Act

for 1911-1912, the sum allotted for all aviation plans was $25,000; today the Navy has become so convinced of the absolute

necessity of a Fleet Air Arm that it is willing, and eager, to spend $27,000 a year on every one of the 30,000 cadets involved

in its training program. And this, of course, over and above the untold thousands of dollars for the training of bombardiers,

gunners, radiomen, navigators, mechanics, and associated specialists and technicians. In 1910 there were no planes; in 1944

there are close to 30,000 of them. Naval aviation has come a very long way in a very short time.

If Lieutenant Ellyson was the first pilot, Captain W. I. Chambers may very well be given the title of the "Father

of Naval Aviation" for the United States. To his undeviating conviction of the value of aviation to the Navy, and to

his untiring efforts to stimulate its development, is due - in large part - the critical decision of the Navy Department to

include aviation among its normal activities.

Most of us - especially in these swift-moving days - are inclined to overlook the simple truism that the first steps in

any new venture are the most difficult - and probably the most important. You can't very well travel two miles, or two thousand,

without somehow getting by the first few feet. So the first steps in naval aviation, well known though they may be, must be

dimmed out through the brilliance of our latter-day achievements. When Mr. Eugene Ely, a civilian pilot, made a successful

take-off from the USS Birmingham at Hampton Roads in November, 1910, the genesis of United States Naval Aviation was begun.

All that has come afterward is in the nature of development.

Mr. Ely completed his contribution to naval aviation two months later when he not only repeated his take-off performance,

but made the first successful landing on a specially constructed flight deck (USS Pennsylvania). From then on developments

continued, less spectacular, but of great cumulative value: Glenn Curtiss equipped one of his planes with pontoons, landed

alongside the Pennsylvania, was hoisted on board, re-lowered to the water, and took-off (January, 1911). Lieutenant Ellyson

took the air from a catapult constructed by the Navy in Washington (November, 1912); a wind-tunnel and model seaplane-basin

were constructed. During the Mexican Incident Lieutenant Bellinger flew on scouting missions over the enemy lines and returned

with valuable information and a plane riddled with bullets. In the meantime an abandoned Navy Yard at Pensacola was converted

into a Naval Air Station.

When World War I broke out, Pensacola had graduated 38 flying-officers, and a ground school had been established at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston. During the period of active American participation in the hostilities overseas,

our Naval aviation contributed much, and learned more. Twenty-two Naval Air Stations were opened in the British Isles, in

France, and in Italy. Operations were exclusively land-based, - for the most part - limited to convoy protection, submarine

patrol, and - in the case of the North Bombing Group - to bombing raids on submarine bases.

Operations such as these, being land-based, were essentially static, while the Navy - practically by definition - is a

mobile service. Airplanes were moving around all right; it was now time to provide bases which would move about, too. The

performance of American naval aviation in the European theater - limited in scope though it was - strengthened the conviction

that the airplane was now at essential component of military armament, and in 1921 a special body, known as the Bureau of

Aeronautics, was created by an Act of Congress, and Rear Admiral W. A. Moffett was selected as its first Chief. This new organization

was to be responsible for "the design," building, fitting out and repair of all naval and Marine Corps aircraft.

Thus succinctly stated, the job seems ordinary enough, but quite obviously, it compels BuAer to be eternally vigilant, seeking

out new features, experimenting with all manner of devices, and adapting proved accomplishments to the specific needs of the

Navy.

During the uneasy period between the two World Wars, the most important accomplishment was, perhaps, the successful solution

of the problem of producing a mobile airdrome. This was done, of course, by the development of the Carrier, which, after all,

is nothing more or less than a well-armed flying-field. The catapult - with its turntable attachment - enables the battleship

or cruiser to serve as an airdrome, but only in a limited degree. A type of vessel whose exclusive function is the housing,

repair, and transportation of aircraft of various kinds - fighters, bombers, observation - would be required and such a type

came into being. But, as usual, after preliminary steps. The Navy, traditionally conservative, took the first step in 1922

when it converted the naval collier Jupiter into a floating airfield and renamed it the Langley. Six years later, two partially

completed battle-cruisers - apparently destined for the scrap-heap by the Washington Treaty for the Limitation of Armament

- were completed as aircraft carriers and joined the Fleet as the Lexington and Saratoga (1928). In 1934 appeared the first

United States naval vessel designed and built from the bottom up as a carrier. This, the first of the pure type carrier, was,

of course, the Ranger, which is still adding to its laurels after splendid performances in the Mediterranean and the North

Sea.

It was in this interim period, too, that the Bureau of Aeronautics experimented with, and finally adopted as its favored

child, the air-cooled engine, now found in every type of naval service plane. There were many other advances, the substitution

of metal alloys for wood in plane construction, the installation of self-starters, of de-icers, retractable landing gear,

and other improvements.

By 1930 most of the basic elements of naval aviation had been put into commission. The years immediately preceding the

fateful September of 1939, when Hitler "cried 'Havoc' and let loose the dogs of war" were characterized by steady

improvements all along the line: in quality of material, in performance of planes and armament, in experiment with new weapons,

new methods of attack - as exemplified by the dive and torpedo bombers - new fields of research, new and efficient methods

of training personnel.

The Navy Department was not indifferent to the fast unrolling of events in Europe. It foresaw the high probability of

American involvement - probably via the German submarine - and its aviation program was quietly shifted into higher gear.

By the time of Dunkerque and the French debacle, the Navy was already knocking at the doors of Congress. Knocking not only

loudly but often. On June 14, 1940, Congress raised the number of authorized naval planes from 3,000 to 4,500. The next day

it jumped the ante to 10,000 and four days later, to 15,000! The last of these Bills (June 19, 1940) contained the useful

clause that this number (15,000) could be exceeded "if, in the judgement of the President, it proved insufficient to

meet the needs of national defense." When Pearl Harbor was attacked the President did so judge and raised the naval air

complement to 27,500.

The Bureau of Aeronautics had not only planned for more planes, but for more men to fly them, more men to fly in them,

and more men to keep the planes in the air. In May, 1940, plans had been prepared for tripling the station at Pensacola both

in size and materiel, and for constructing even larger schools at Jacksonville, Miami, and Corpus Christi. When the goal of

27,500 planes had been set up, BuAer implemented this with a colossal plan to train 30,000 pilots a year, as well as a proportionate

number of technicians and other aviation personnel. Seventeen Flight-preparatory, 90 War Training Service, five Pre-flight,

13 Primary and two Intermediate Schools reflect the speed and efficiency with which the Bureau of Aeronautics has transmitted

a plan into a performance.

Many of us in Naval aviation are so close to our jobs at some particular activity that we are apt to lose sight of other

significant aspects of the air arm of the fleet which occupy the time and the brains of the Bureau of Aeronautics. There is,

for example, the Lighter-than-air branch with permanent bases in New Jersey and California; there is the Photographic Division,

providing invaluable data for pre-operational strategy and reliable information of operational achievement; there is the Naval

Air Transport Service, carrying seven million pounds of mail and cargo every month over 60,000 miles of regular and established

routes; there is the Aerological service, which not only gives daily - or, rather, four-times-daily - reports on current weather

conditions, but tabulates and files an infinity of reports for future analysis and the construction of a sounder science;

and there is the Medical Research Division, devoted to the study of the physiological and psychological effects of flight

upon personnel - the nature of anoxia, of vertigo, of "blackouts," and the rarer but more deadly "redouts,"

of fatigue. The Bureau of Aeronautics is a very versatile body.

There is little need to call attention to the more than obvious fact that air-power is of the very highest importance

in modern war, or that naval aviation has carried off - and continues to carry off - its share of the laurels. In every theater

of war, and on every ocean, naval aviators have given a good account of themselves. They have tracked down the deadly submarine

and reduced it from a menace to a hazard; they have provided safe convoy for thousands of ships through waters once infested

and now comparatively safe; they have reduced to hopeless rubble enemy naval bases beyond the reach of naval guns; they have

provided essential coverage for the many successful landings in the Pacific (North and South) and in the Mediterranean, and

they can be relied upon to supply equal protection to future landings; they have been exceptionally efficient life-savers,

and have rescued more than half of the men who have baled out and landed in the sea. With the great increase in the number

of "baby-carriers," they will be much more in the news and over many more sections of the deep-blue water.

Naval aviation - the Navy's adopted child - has won an envied and honored place in the Navy family. By its demonstrations

of ability and efficiency, it may even claim to have brought about one of the rare revolutions in naval tactics. Certain it

is that the actions at the Marshall and Gilbert Islands and at Bougainville raised the carrier to the Number One position

on the priority list of naval construction, and it cannot be without significance that a new office, that of Deputy Chief

of Naval Operations (Air) has been created. The engagements in the Coral Sea, at Midway, and in the Solomons demonstrated

that the Bureau of Aeronautics was right in emphasizing ruggedness of construction, adequate armor and high fire-power at

the possible expense of speed and maneuverability. The Bureau of Aeronautics is not less right in its determination to see

that its naval aviators shall continue to be the best trained and best equipped pilots aloft.

Naval Air Highlights, September 1908 - February 1944

1908 September. Demonstration by Orville Wright at Fort Myer, Virginia, witnessed by official Naval Observers. This flight

lasted one hour, two minutes, and fifteen seconds. Naval observers recommended, unsuccessfully, the construction of an airplane

equipped with pontoons.

1910 November 14. Mr. Eugene Ely, civilian pilot for the Curtiss Company, made the first take-off from the deck of a naval

vessel-the USS Birmingham-at Hampton Roads.

1910 December 23. Lieutenant T. G. Ellyson, USN. ordered to report to the Curtiss Company at San Diego for flight instruction. Lieutenant

Ellyson became Naval Aviator No. 1.

1911 January 18. Mr. Ely made the first landing on the deck of a naval vessel-the USS Pennsylvania-at San Francisco.

1911 February 17. Successful demonstration of a hydroplane. Glenn Curtiss lands alongside the Pennsylvania, is hoisted

on board, relowered to the water, and then takes off and returns to his base.

1911 Match. Naval Appropriation Act for 1911-1912 allocates $23,000 for aviation. Captain W. I. Chambers, USN, detailed

to establish a naval aviation service.

1912 May 21. Organization of the United States Marine Air Corps.

1912 September. Catapult take-off attempted at Annapolis. Unsuccessful.

1912 November 12. Lieutenant Ellyson makes a successful take-off from a catapult devised by Naval Constructor H. C. Richardson.

1913 Aviation unit, shore-based at Guantanama, cooperates with The Fleet on winter maneuvers.

1914 January. First United States Naval Air Station established at Pensacola, Florida. Commanding Officer, Commander H.

C. Mustin, USN.

1914 April. Naval planes on scout duty during the occupation of Vera Cruz. One plane damaged by enemy fire.

1917 May. Organization of the "Marine Aeronautics Company."

1917 November 13. The French Coastal Unit made the first naval aviation patrol flight in the European war theater.

1917 November 28. First Navy factory for the construction of aircraft completed.

1919 May 31. The seaplane NC-4 arrives at Plymouth, England, on the last leg of its flight from Newfoundland, and becomes

the first airplane to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

1921 July 12. The Bureau of Aeronautics created by Act of Congress.

1922 October 26. First take-off made from the USS Langley, The Langley, the converted Collier Jupiter, was the Navy's

first carrier. It was also the Navy's first electrically driven vessel.

1923 October. The USS Shenandoah, the Navy's first dirigible, put into commission.

1926 June 24. The Five Year Building Program authorized by Act of Congress. This program contemplated the training of

sufficient personnel to maintain and By a fleet of 1,000 planes.

1932 September 23. Navy airmen win the International Gordon Bennett Balloon Race (Switzerland). Time aloft: 41 hours.

1933 September. Navy squadron establishes world formation flight record (Norfolk, Virginia, to Coco Solo, Canal Zone-

2,059 miles).

1933 November. World record stratosphere balloon ascent set by Navy personnel: height, 61,237 feet.

1934 January. Navy squadron non-stop flight from San Francisco to Pearl Harbor, 2,450 miles.

1934 June 4. USS Ranger placed in commission. The Ranger was the first United States vessel specifically designed and

constructed as a carrier.

1934 December 8. Dedication of Cory Field, Pensacola.

1935 June 5. Act of Congress authorizes the commissioning of Technical Aviation Officers.

1936 April 4. USS Yorktown launched.

1938 May 12. The U. S. S. Enterprise placed in commission.

1939 July 1. The Wasp Air Group formed and assigned to the Wasp.

1940 June 14-19. Congress increases the authorized complement of Navy planes from 3,000 to 15,000, and permits the President

to exceed this by the number required for national defense. Under this elastic provision, the present goal of 27,500 planes

was set up.

1942 February 1. Raid on the Gilbert and Marshall Islands (Yorktown and Enterprise).

1942 February 24. Raid on Wake Island (Enterprise).

1942 March 10. Raid on Salamaua and Lae (Lexington and Yorktown).

1942 April 18. The raid on Tokyo. This venture was unique in that, for the first time, medium land bombers were transported

across an ocean and then launched off enemy shores.

1942 May 4. The raid on Tulagi (Yorktown).

1942 May 7-8. The Battle of Midway (Hornet, Enterprise, and Yorktown). This battle, which restored the balance of naval

power in the Pacific, was the first decisive defeat suffered by the Japanese Navy in 350 years. The Yorktown was lost.

1942 August 23-25. The Battle of the Eastern Solomons (Saratoga and Enterprise).

1942 October 26. The Battle of Santa Cruz Island (Enterprise and Hornet). The Hornet was sunk.

1943 November 5. The first large scale attack on Rabaul.

1944 January 30. The attack on the Marshall Islands.

1944 February 17. The Truk raid.

1944 February 23. Raid on Saipan. Tinian, and Guam.

The Story of Floyd Bennett Field

(pages 16-17)

The story of Floyd Bennett Field, from garbage heap to United States Naval Air Station, is a story of progress and achievement

that has only just begun. Now an important cog in the prosecution of the world's greatest war, it will emerge in a peaceful

world to rebuild aviation for the good of mankind.

During World War I, the officers and men of the U.S. Naval Air Station, Rockaway Beach, flying harbor patrol in their

box kite flying boats, couldn't foresee that Barren Island, just across the bay, with its garbage heaps and glue factory,

would one day become the U.S. Naval Air Station of World War II.

Some ten years later, when the City of New York undertook the tremendous task of filling in Barren Island and constructing

a municipal airport, there was still no hint of its future military role. NAS, Rockaway Beach, had long since been decommissioned.

A Naval Reserve Aviation Unit which had been in operation at Fort Hamilton, NY, during the early 1920s, was moved to the site

of NAS, Rockaway, in 1926, and to Curtis Field, Valley Stream, in 1929, made preparations to locate at the new airport. But

the field was primarily a municipal project, and the Reserve Unit was for the sole purpose of providing Naval Aviation training

for reserve aviators.

Perhaps it was destiny then that stepped in and gave the new airport a Navy name. It was dedicated in May 1931, as Floyd

Bennett Field in honor of a Navy Warrant Officer who lost his life in an unselfish attempt to rescue three fliers whom he'd

never seen.

Warrant Machinist Floyd Bennett, born in Lake George, New York, made aviation history in 1926, when he and Admiral Richard

E. Byrd became the first persons to fly over the North Pole. For this flight the two aviators were awarded the Congressional

Medal of Honor, but already they were planning a second such flight - this time over the South Pole.

Floyd Bennett didn't live to realize the triumph of the South Pole Expedition. In 1928, while suffering from a burning

fever, he took off from Detroit to go to the aid of the Irish German crew of the "Bremen", which was forced down

at Greenley Island, Quebec, on an attempted non-stop flight from Europe. At Murray Bay, he was stricken with influenza, but

refused to turn back. Halfway on his journey across Canada, Bennett died of pneumonia.

In the ten years from the dedication of the Municipal Airport to the commissioning of the U.S. Naval Air Station, many

aviation firsts were credited to Floyd Bennett Field.

Wiley Post flew the "Winnie Mae" around the world in seven days, 18 hours, and 49 minutes in 1933, a record

topped in 1938 by Howard Hughes, who flew from Floyd Bennett a distance of 14,824 miles around the world in three days, 19

hours, and 17 minutes.

Other famous flights included the Russell Boardman - John Polando flight from Brooklyn to Turkey; Clyde Panghorn and Hugh

Herndon from Brooklyn to Wales; Jimmie Mattern and James Griffin from Brooklyn to Russia via Newfoundland; Rossi and Codos,

French fliers, who established a long distance record from Floyd Bennett to Syria.

The peacetime activities of the Municipal Airport, however, began to taper off in early 1941. Following the spectacular

successes of the German Army and Luftwaffe in Poland, Norway, the low countries, France, and over London, it became increasingly

apparent that steps to insure American preparedness would have to be accelerated. The expansion of the Aeronautical branch

of the Navy was part of that preparedness program, and planes began to flow in a steadily increasing stream from the manufacturing

plants to the Fleet. It was out of these conditions that the Naval Air Station, New York, emerged.

The transition of the field from a Municipal Airport to a Naval Air Station was accomplished during April and May of 1941.

On May 26, the field was officially leased by the Navy Department, and commercial flying ceased. It was decided that the Naval

Reserve Aviation Base should be continued for a time, but the air station absorbed many of the pilots of the reserve unit,

and, by the end of the summer, the NRAB had ceased to function.

The first entry in the log book of the air station was made on June 2, 194l, indicating that at the time of commissioning

the personnel consisted of six officers and 24 enlisted men in addition to the Skipper - Lt. Commander Don F. Smith, USN,

now a Captain and Director of the Naval Air Transport Service.

The first two months of operation were mainly devoted to the organization set up, and by the middle of August, Commander

Smith was relieved by Commander E.O. McDonnell, USNR, now also a Captain and Skipper of an aircraft carrier.

A little later the purpose of the new station was affirmed by the statement of general policy contained in station regulations:

"...to provide base facilities for the Fleet and the North Atlantic Naval Frontier and to assemble, service, equip,

and deliver naval aircraft from factory to Fleet."

After Pearl Harbor, Floyd Bennett Field experienced its greatest expansion. In February of 1942, the field was purchased

outright from the City of New York for $9,250,000. The field was expanded in size from 387 acres to 1,288 acres by reclaiming

large portions of Barren Island. Several miles of roads were added, long concrete runways were installed, and work was begun

on a new seaplane hangar and other facilities for beach¬ing Navy flying boats. The enlisted mens barracks, the recreation

hall, the mess hall, bachelor officers quarters, supply building, and numerous smaller buildings were under construction.

During most of this period of construction and expansion, Capt. McDonnell remained as Skipper of NAS, NY. In February

1943, he was relieved by Capt. Kenneth Whiting, USN, a pioneer Naval Aviator and sometimes referred to as the "Father

of the Aircraft Carrier". But Capt. Whiting's stay at Floyd Bennett Field was tragically short. On April 23, while on

official business in Washington, he died.

Capt. Newton H. White, Jr., USN, present Commanding Officer, reported aboard May 17, 1943. His record speaks for itself,

and his friendly, efficient guidance has coordinated the ever-increasing activities of Floyd Bennett Field into a smooth functioning

and vital part of the war machine.

The increase of personnel at NAS, NY, matched the physical expansion of the field. From the six officers and 24 enlisted

men present at the commissioning, the station's personnel today mans eleven separate departments of the Naval Air Station

itself, in addition to several other large activities now located at Floyd Ben¬nett.

The huge Aircraft Commissioning Unit handles the receipt, equipping, and checking of hundreds of naval aircraft per month

from eastern factories. Service functions for the station are performed by the Public Works Department; Fire and Safety Engineering;

Station Intelligence and Security; Supply, Commissary, and Disbursing; Medical and Dental; and Communications.

The Gunnery Department has cognizance over all explosives. The Operations Department consists of a Flight Division which

administers to all station aircraft; Aerological Division which handles weather forecasts; and a Boats Division which takes

care of any necessary aquatic functions. The Training Department conducts many courses in flight and gunnery problems for

both officers and enlisted men.

Several aviation units of the Atlantic Fleet, known as the Fleet Air Detachment, are using the facilities of the air station.

A Hedron unit services three operating squadrons which fly patrol duty. A Scout Observation Service Unit is also stationed

here.

The ferrying activities of the station and the operation of various Ferry Service Units at different points in the country

are controlled by the Naval Air Ferry Command, with headquarters at Floyd Bennett Field.

NAS, NY, is an important point of origin in the trans shipment of naval air borne cargo. Detachments of two squadrons

of the Naval Air Transport Service operate at the air station and maintain a point of contact with overseas transport activities.

In a scant thirteen years, Floyd Bennett Field, former garbage heap, has served notably in peace and in war. Aviation

is on the threshold of a new era, with rockets, helicopters, and other innovations yet to be developed. May the future of

Floyd Bennett Field be as great as its past.

Naval Air Ferry Command, Floyd Bennett Field

(pages 88-89)

The Naval Air Ferry Command, commissioned 1 December 1943, was established as a coordinating agency over all naval ferry activities.

Its primary duty is the safe and expeditious delivery by flight of naval aircraft that must be moved to the embarkation points

for further delivery to the U.S. Fleet and to the training and other commands. Its function is to direct, control, and regulate

the ferrying of new production naval aircraft within the continental United States, and outside the United States and overseas

as may be directed. It also is charged with ferrying aircraft other than new production as may be directed from time to time.

The command is constituted as an air wing of the Naval Air Transport Service and is responsible directly to the Chief of Naval

Operations through the Director, Naval Air Transport Service, for all ferrying activities.

The headquarters staff under Captain John W. King, USN, was initially formed in Washington. On 2 January 1944, headquarters

were moved to Naval Air Station, New York. The Ferry Command consists of Air Ferry Service Squadron One (VRS 1) and Air Ferry

Squadron One (VRF 1), located at Naval Air Station, New York; Air Ferry Squadron Two (VRF 2), Columbus, Ohio; and Air Ferry

Squadron Three (VRF 3), at Naval Air Station, San Pedro, California. [Air Ferry Squadron Four, Floyd Bennett Field, was commissioned

after this book was published].

Prior to the establishment of a separate command to coordinate and regulate all naval ferrying activities, delivery of

new aircraft was accomplished by aircraft delivery units, the predecessors of present air ferry squadrons. With the tremendous

increase in aircraft production, a coordinating agency was essential. Among the major innovations were the establishment of

ferrying routes with planned ferry stops where servicing and repair units under VRS 1 were located, permitting rapid delivery

of aircraft to the fleet commands; organization of a complete transcontinental communications system; stationing of selected

and trained naval ferry control liaison officers along all ferry routes who acted as staff representatives in the field for

the clearance and safeguard of ferry flights, accommodation of pilots, observance of flight rules established by the command,

and the maintenance of records and communication of daily reports, including action in accidents en route.

The Command has expanded with the increase in the production of aircraft and the assumption of ferrying assignments formerly

handled by fleet and other commands or under civilian contracts, until the air ferry squadrons became the largest squadrons

in naval history from the standpoint of numbers of pilots.

VRF-I

Commissioned 1 December 1943 under Commander Laurence D. Ruch, AV(G), USNR, Air Ferry Squadron One ferries all new naval

aircraft produced on the Eastern Seaboard and more than its share of "War Wearies" returning from the fleet, honorably

discharged.

The squadron was furnished with its nucleus of experienced personnel - some 250 pilots - by its predecessor, Aircraft

Delivery Unit of Naval Air Station, NY, the same ADU which, a few months after Pearl Harbor, had but ten pilots permanently

assigned to it. Within three months after being commissioned, the squadron more than doubled in size. In March 1944, 1,049

pilots were assigned to it, 550 permanently. Monthly deliveries of aircraft tripled within the same period.

For the first 18 months of the war the New York ferry pilots delivered all new VF and VTB aircraft used by the fleet.

Since then they have continued to deliver all new VTB and the overwhelming majority of all VF aircraft.

It has not been an isolated instance for a ferry pilot, transferred to the Fleet, to be assigned an airplane one of his

mates delivered. In at least one case, a combat pilot was assigned an aircraft he himself had ferried. In another instance,

a VRF 1 pilot was proud to ferry back a "War Weary" Wildcat decorated with 26 Jap flags - an aircraft he had originally

delivered to the Fleet.

Of the many pilots furnished to the fleet by VRF 1, one earned the Navy Cross three days after earning the Distinguished

Flying Cross.

On several occasions, the Squadron has been proud to earn and receive a "Well Done" for the safe and expeditious

movement of a group of high priority aircraft. When the Fleet needed them, VRF 1 delivered them!

When the figures are available, VRF 1 will be proud to reveal the extraordinary safety with which its magnificent record

was made.

The Glory Board is the outstanding decorative feature of VRF 1's "Ready Room"; each pilot of the squadron is

listed. Ferrying the equivalent of five trips from coast to coast without damage to aircraft entitles him to the display of

a pair of Navy wings. The fifth such entitles him to a streamlined stork, the squadron insignia. With each stork goes a ribbon

for the twenty five trips made without damage.

VRF 1, in addition to its regular ferrying activities, mans and operates a Training Division at NAS, Willow Grove, PA,

where all pilots assigned to the Naval Air Ferry Command receive their initial ground and flight training.

When war came upon us, time did not permit the training of adequate numbers of Naval Aviators from scratch to handle the

tremendous task with which the Navy was confronted. The civilian pilots responded. VRF 1 today has in its complement, engineers,

teachers, lawyers, accountants, students, salesmen, newspaper re¬porters, test pilots, skywriters, combat pilots of the Navy

and RAF, aircraft and auto dealers, policemen, firemen, executives in all kinds of business, etc.- now Naval Aviators all

- ferry pilots all. A-V(N)s, A-V(T)s, A-V(G)s, USNs all united in a common task - the safe expeditious delivery of combat

aircraft to the Fleet.

VRS-I

Commissioned 1 December 1943 under the command of Lieutenant Richard S. Cott, A-V(S), USNR, upon the establishment of

the Naval Air Ferry Command, Air Ferry Service Squadron One maintains its headquarters at Naval Air Station, New York. Consisting

of four ferry service units at its inception, its function is to administer and control all ferrying repair and service activities.

Originally formed from the engineering section of the predecessor aircraft delivery unit, this squadron experienced a

phenomenal growth, now numbering 13 field servicing units, a West Coast detachment of headquarters at San Diego, California,

and ferry materiel liaison officers at the important supply depots at Norfolk and San Diego. Personnel have more than tripled

in size in the first ten months of operation.

Ferry service units, and auxiliary units, are established at all main ferry stops on the transcontinental and coastwise

ferry routes. Consisting of a naval aviator in charge, and engineering officers as assistants, and with highly trained technical

aviation ratings, these units rapidly service and repair aircraft in a ferry status. Salvage and rescue in the event of crashes

is another important function.

The nerve center of the squadron is at Naval Air Station, New York. It is charged with procurement and transport of all

required spare parts, the allocation of gasoline, procurement of tools and transportation equipment for the units, and maintenance

of all records and reports. A small cargo airline is operated by this squadron to expedite delivery of parts and personnel

to field units.

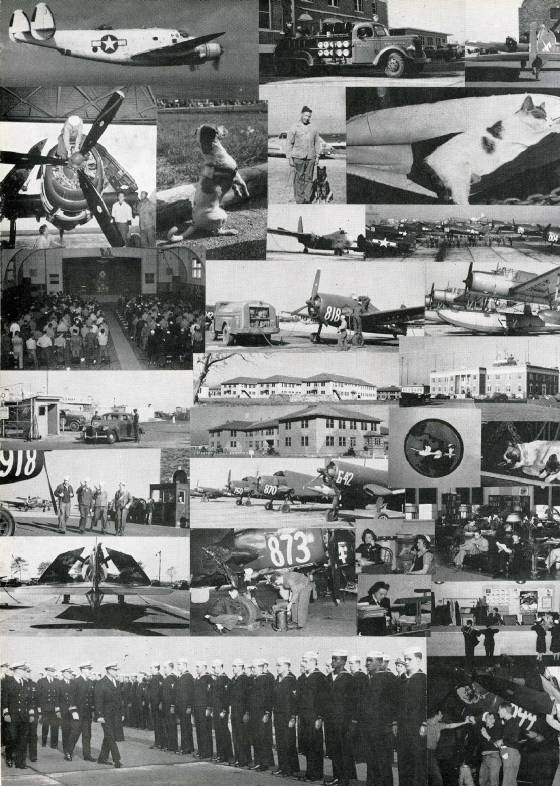

Scenes of NAS New York, 1944

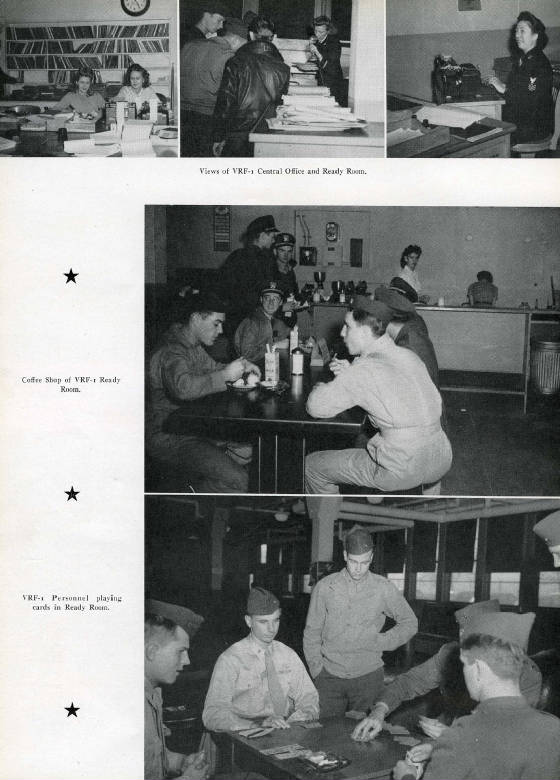

VRF-1's Office and "Ready Room"*, Hangar 9, 1944

* "Ready Room" was where pilots waited between flights.

|